"The Future. Today." boasts a rusty billboard in Batticaloa.

The coastal town in Sri Lanka’s troubled eastern province is at the centre of a renewed military campaign to drive out the separatist forces of the Tamil Tigers (LTTE). From bases around the district and from the town itself, government artillery bombard suspected LTTE positions day and night. For every new area levelled by the artillery, an influx of refugees arrive in the town with nothing but the clothes on their back.

The heavy military presence has done nothing to stop the killings and abductions of civilians that occur with terrorising frequency; the streets are dead quiet after dark, punctuated only by the pounding of artillery and the roar of rocket launches. The cellphone service advertised by the rusty billboard has been shut down as a security risk. With the 2002 ceasefire now broken in everything but in name, the future is not here today, and many Sri Lankans fear that it will not come tomorrow.

Looming crisis

In the past month, an estimated 60-80,000 refugees from the district have arrived to joined the 90,000 who were displaced by earlier offensives. The massive influx has swamped NGOs in the region and pushed infrastructure beyond its limits.

“There're huge gaps in terms of food, safe drinking water and sanitation provisions,” says UNICEF’s Head of Office in Batticaloa Christina de Bruin. “The overcrowding is causing concerns for basic hygiene in the camps.”

“Agencies such as the UN are trying to respond to these huge needs, but there's still a long way to go because of the sheer number of internally displaced persons that have come in a very short timeframe.”

The UN’s World Food Program says that without additional funding, they only have enough supplies to feed the refugees until the end of April. With more refugees likely to become displaced over the coming weeks, the situation could quickly become a full-blown humanitarian disaster.

For now, the refugees are happy to be here – anywhere, as long as it is away from the fighting. In one camp, the refugees take shelter under the only two trees to escape the scorching sun. An old woman and her family watch over their sick infant as he sleeps inside the tent, which they share with four other families – seventeen people in all.

Twelve days prior, their village was shelled without warning. “There was no time to collect anything,” says the old woman, “only the children.”

Nearby, three sisters and their families are lucky to be alive. The shelling in their area started three weeks ago. The entire village took shelter in the local temple, in the hope that the gods would protect them.

The army used their multi-barrel rocket launchers – capable of launching 40 rockets in one salvo – to attack LTTE bases in the area. One of the rockets exploded close to the temple. Some of the villagers lost limbs in the attack. “I heard someone was killed, too,” one of the sisters says, “nobody knows, there were body parts everywhere.”

Like the other refugees, they scattered and fled. Nobody stayed to find out for sure.

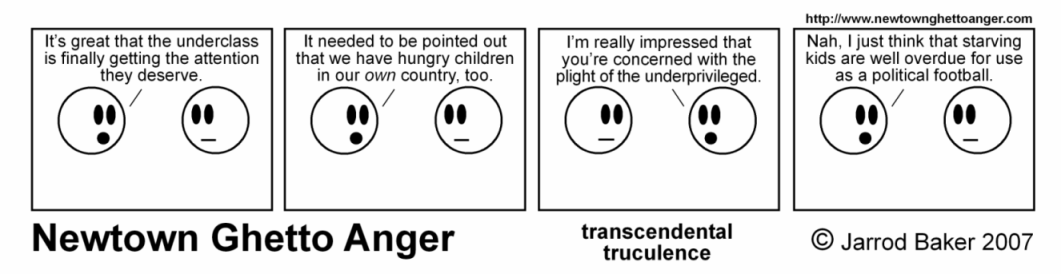

Political fodder

Around the numerous camps, refugees share the same dilemma: They fear for their lives if they return home, and they fear for their future if they stay at the camp.

“How are we supposed to bring up our children here?” asks a farmer, gesturing at the crowded camp. The latest round of displacements came during harvest – most of the crop was harvested, but little had been sold. Looters have probably taken most of it now, the farmer laments. He has lost the entire season’s work, but, like everyone else, he can only hope that his home and equipment will still be there when he returns to rebuild his life.

What will he do if there is nothing left? He does not know, but there is nothing he can do about it in the camps.

Refugees from the Vaharai region, some of whom have been displaced for eight months, are now having their return fast-tracked. Many of them had been forced to flee once before, when the tsunami struck. One fisherman says that his house, built with international aid after the tsunami, has been destroyed again. Many people from his village were killed by shelling and crossfire as they fled down the coast; he will not go back until he is sure it is safe.

The government is under pressure to solve the refugee problem in Batticaloa and to re-populate areas captured by the military. They want to see the refugees returned as soon as possible. But despite government assurances that Vaharai has been cleared of the LTTE, many refugees believe that the LTTE are simply hiding, and will resurface once the civilian population returns.

These refugees understand their political value. In LTTE territory, they are human shields. If the government tries to avoid killing them, this gives the LTTE a tactical advantage; if the government does not, their deaths give the LTTE a propaganda victory. In government territory, their flight is trumpeted as an escape from the clutches of the LTTE and a vote of confidence in the government; their return will be confirmation that the government is in control.

The refugees trust neither side. They confirm that the LTTE were operating near their homes. “But they do not come into the village,” they are quick to add. An identical, practiced response is found in every camp: The LTTE operates close to villages, but they do not harass the villagers, and the villagers do not give them support.

For now, they feel safe in Batticaloa. The artillery pound away in the background, but they are unconcerned: The shells are landing somewhere else, after all. More importantly, they are under the watchful eyes of the UN and dozens of NGOs, and they are keenly aware of the difference that international pressure can make.

“Help us stay here,” one woman pleas when she sees my camera and notepad, “we are depending on the international people.”

Their concern stems from growing reports of refugees being relocated by force or by threats of cutting off their food rations and land seizures. Some of these relocations have separated families, left women and children to fend for themselves, with no way for the family members to contact each other.

As I talked to the camp manager, two soldiers arrived. Upon seeing me, they gave a sheepish grin and left immediately. The refugees say that they were there to collect names and places of origin, in preparation for relocation.

UNICEF is monitoring the camps for forced relocation and the refugees have been given emergency numbers to reach UNICEF and UNHCR if the government tries to force them to return; but with the cell service shut down and no landline, the refugees are helpless.

An unlikely survivor

Life in the camps is virtual imprisonment. Men and women sit aimlessly from one day to the next, wondering what is left of their old lives and if they will ever be able to resume it. But one small island of normalcy can be found in these camps: Less than two weeks after their arrival, still living in tents and with the most basic of amenities, the children are going to school again.

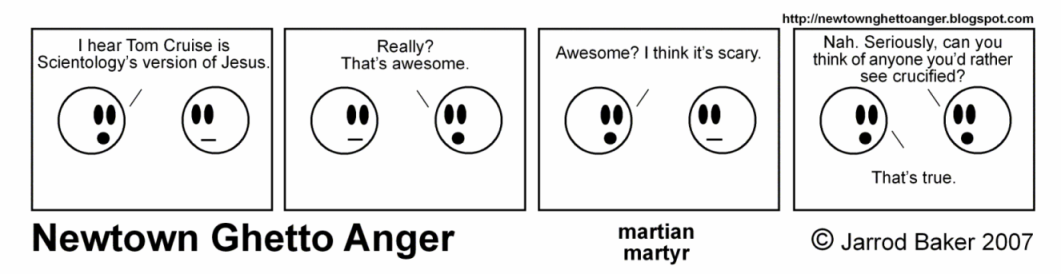

Education has been the most unlikely survivor of the civil war. Despite nearly a quarter-century of bloody conflict that has claimed over 68,000 lives, Sri Lanka still has a literacy rate of 92% – one of the highest among developing nations. Even deep in the Vanni, the heavily-militarised region controlled by the LTTE, the Sri Lankan government continues to fund and operate public schools.

The way in which education transcends the bitter divisions in Sri Lanka is noble, yet bizarre. One principal in Kilinochchi, the administrative capital of the LTTE, asked UNICEF to help them reinforce their school’s bunker. The principal is a civil servant on the government payroll, and the bunker was to protect the students from government bombing and shelling.

The importance of education for Sri Lankans is such that, even as the refugees flee across the country, the thought of schooling is not far behind. When the fighting started last August, local education directors expected children from 15 schools to be displaced and appealed to UNICEF for makeshift school buildings. Before the refugees arrived themselves, schools were being set up for their children.

A veteran of these displacements, Kanthasamy now works as an emergency education consultant for UNICEF. During his time as a government education director in the northern city of Jaffna, the LTTE-held city fell to government forces; the LTTE forced a massive exodus, leading more than 350,000 civilians into areas that the LTTE still controlled. He and his colleagues established over a hundred new schools within three weeks.

In the effort, principals lost their lives retrieving books, documents and even furniture from their old schools. “It’s a committed life,” says Kanthasamy, “you need a bit of sacrifice to be a teacher here.”

Aside from the cultural importance of education, schools take on a special role in chaos of refugee life. “With the movements of people, concerns over security in the communities and in the camps, the school should be an oasis for these children,” says Rachel McKinney, the coordinator for UNICEF’s Emergency Education Program.

“Physically, it provides them with basic shelter. Emotionally, it provides them with support that they don't necessarily get in the camps and in the communities, because everyone around them is stressed. Their parents might not be able to provide the same support as they used to. Their friends might have been displaced to another area. Tensions are high all around, and so the school should really be a place where they can just be a child again.”

New Zealand has provided $1.3m for UNICEF’s emergency and catch-up education programmes. This money has helped to provide study material and stationary for the children, as well as assistance to get the schools up and running. It also provides additional support for children who have missed a significant part of their education to prevent them from falling through the cracks.

“In some areas [in Vaharai], teachers could not get in for up to six months,” says McKinney. “For the last two terms, children there did not attend school. They can't perform at grade-level. They can't compete. And there's a cultural barrier against children repeat grades, because they're age-specific grades and age-specific examinations.”

The catch-up education programme has been working to produce a condensed curriculum to bring these children back up to speed. However, the renewed violence and massive displacements is throwing the education system – along with everything else in the Batticaloa district – into chaos once again.

Many classrooms in Batticaloa are now filled to the brim with refugee families and their few possessions. 19 schools in the district have been converted into makeshift camps by the desperate refugees. There is no place to teach the 13,000 students from these schools, and to compound the problem, another 30,000 new students have poured into the district. Some of the students from Vaharai are being returned to their homes, whiles others are being mixed with the new arrivals.

“[The new influx] drew on resources that were already stretched,” says McKinney. “We were under the assumption that [the catch-up education programme] would have access to these children in the same places of displacement … for up to six months. Now you have everyone lumped on top of each other, with many different types of problems, and an incredibly stressed education system.”

Even as NGOs, teachers and planners struggle to maintain education standards, the harsh realities of the Sri Lankan civil war are never far away.

In areas where the government jets drop their bombs, parents keep their children home. For a short time at least, notes Kanthasamy. After a few weeks, people get used to it and run out only to see where the bombs are going fall.

Back in Batticaloa, a multi-barrel rocket launcher has been positioned in the military camp close to a cluster of the town’s best schools. As the rockets blast off with a long series of deafening roars, students faint from fright. Cracks are beginning to show on the school’s walls, as well as on the teachers’ and students’ nerves.

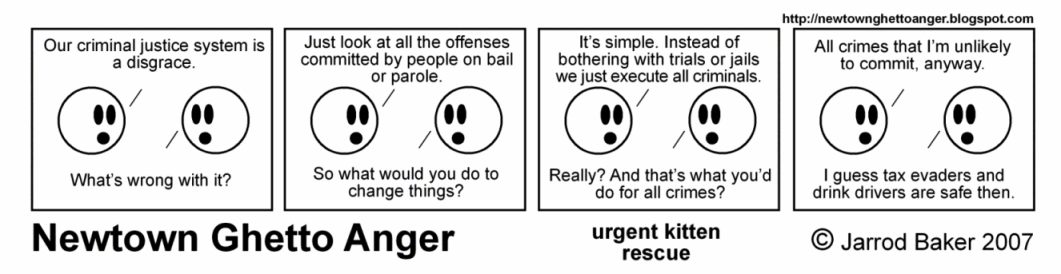

The most terrifying threat of all is forced conscription. The LTTE has long been accused of recruiting child soldiers, but in the east of the country, where it is weakened and in retreat, another threat has emerged. The breakaway LTTE faction, led by former-LTTE commander Colonel Karuna, is now operating with impunity in Batticaloa.

Allan Rock, a special adviser to the UN representative for children and armed conflict who visited last year, claimed that the Karuna faction was responsible for the forced recruitment of children, and that the Sri Lankan army was guilty of complicity and even participation. The government denied the accusation and branded Rock as an LTTE sympathiser.

At the very least, the army has turned a blind eye to Karuna’s activities. In Batticaloa, the smoking guns are toted around in broad daylight. Armed men in civilian clothing – Karuna’s men – roam the streets. Occasionally they are seen casually chatting to government soldiers. Even more brazenly, offices for the Karuna faction sport 10-foot high signs with bright red and yellow logos, and are located adjacent to army checkpoints.

Abductions are taking place from the streets, from refugee camps, as well as from the homes of Batticaloa residents. In a report earlier this year, Human Rights Watch claimed that the Karuna faction had abducted at least 200 children from Batticaloa, and estimated that it could be as many as 600.

If the war continues, the future of these children may look the same as today.